A Louisiana jury returned a $411 million verdict against industrial contractor Brock Services after a 20-pound scaffolding bar crushed Jose Valdivia's skull and spine at a Phillips 66 refinery. This makes it the largest single-plaintiff personal-injury award in the state's history.

Valdivia is now wheelchair-bound with severely limited speech, representing catastrophic loss that drove the trial's valuation framework.

Plaintiff's evidence of systemic safety neglect collided with insurers' refusal to settle, creating parallel coverage disputes that pitted excess carriers against each other. The judgment set a new benchmark for personal injury awards in Louisiana and has attracted industry-wide attention for its potential implications.

Brock Services Lawsuit Case Background

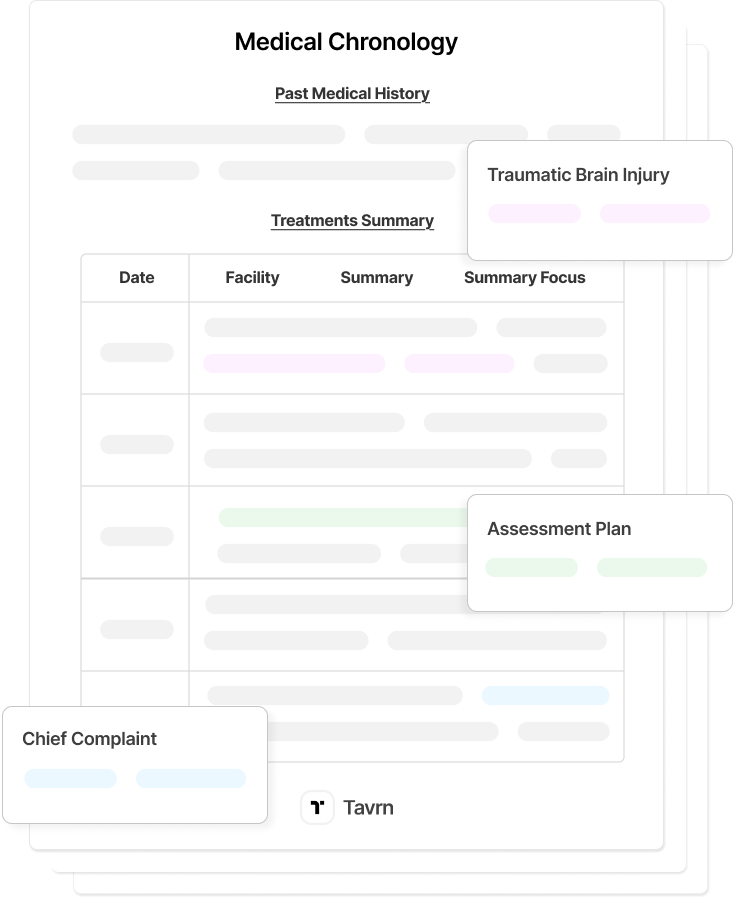

This record-setting verdict grew from a single, narrowly documented event inside an otherwise routine refinery maintenance project. Understanding how that moment translated into a $411 million judgment requires examining the physical mechanics of the accident, Brock Services' role on site, and the paper trail that followed.

The Incident

On an August afternoon in 2022, Jose Valdivia was working beneath a scaffold at the Phillips 66 refinery in Lake Charles, Louisiana, when a 19-pound metal pipe slipped from the structure and struck the crown of his hard hat.

Standard personal protective equipment could not prevent the direct impact from causing diffuse axonal brain injury and traumatic spinal damage that left him permanently wheelchair-bound with severely limited expressive speech.

Video admitted at trial showed paramedics stabilizing Valdivia's cervical spine before rushing him to emergency neurosurgery; he remained hospitalized for weeks and later required full-time attendant care.

Safety Findings

Routine dropped-object netting had not been installed over Valdivia's work area, a lapse plaintiffs argued made the harm "certain to occur."

Trial evidence revealed a lean supervisory structure: one foreman monitored multiple elevated work stations, including the scaffold that failed. Co-workers testified that a colleague—referred to internally as a "walking hazard"—had repeatedly mishandled scaffold components in the days before the accident, yet no disciplinary or retraining measures were documented.

OSHA logs produced in discovery listed only minor first-aid cases for the prior year, a statistic that plaintiffs contrasted with witness testimony describing near-miss incidents that were never formally reported.

Critical Documentation Gaps

Early records documented Valdivia's injuries as severe and life-altering, and there is no indication that they were characterized as 'non-life-threatening' in incident reports or insurance notices.

The refinery filed its OSHA-required Form 301 two days late and omitted the mechanism of injury, forcing plaintiff counsel to reconstruct the sequence through co-worker emails and cell-phone photos.

Missing scaffold inspection checklists, incomplete daily hazard analyses, and an unsigned job-safety briefing revealed a pattern: critical documents existed when they favored Brock's defense but disappeared when they confirmed risk.

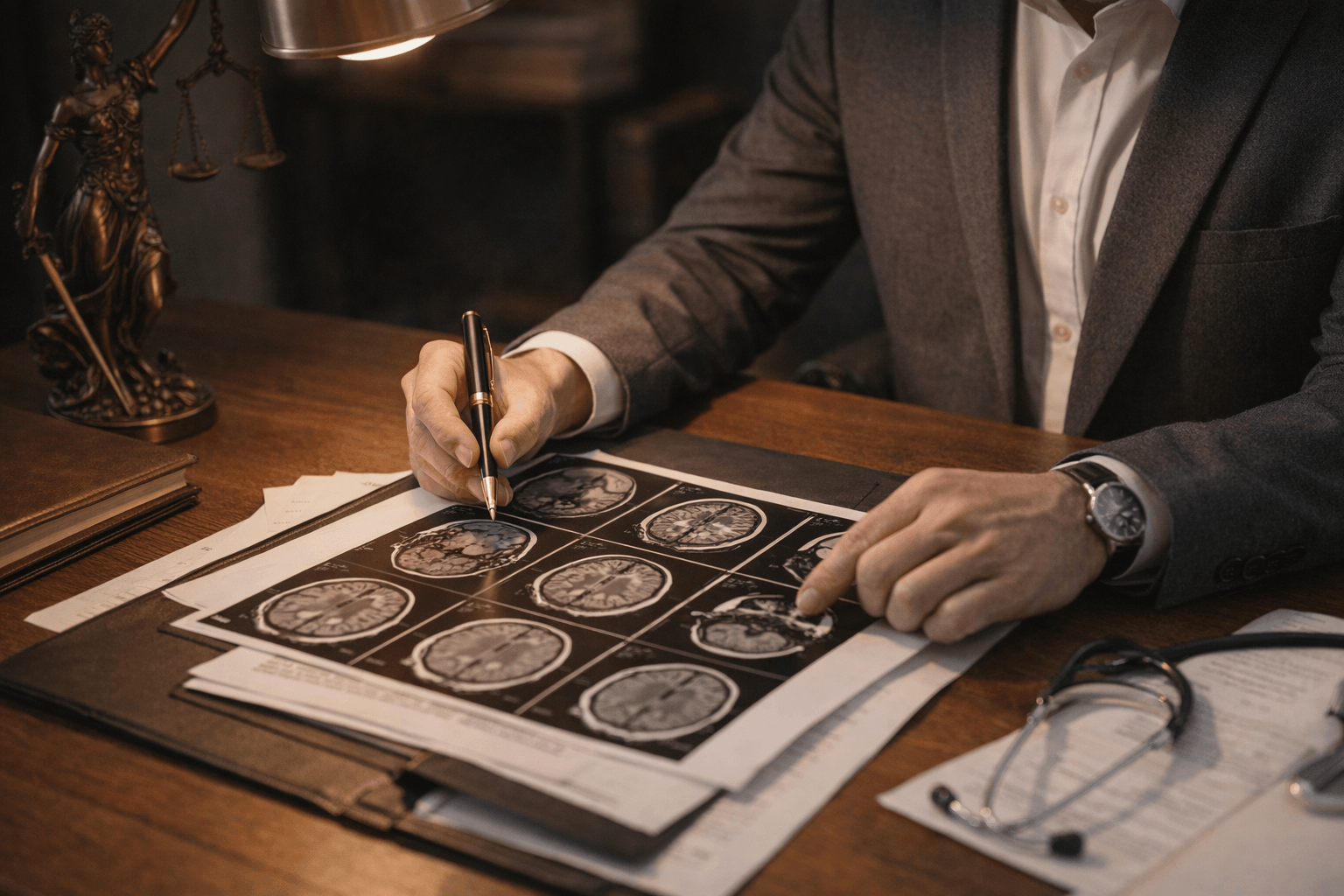

By the time medical experts presented MRI scans showing irreversible cortical damage, the disconnect between minimal paperwork and catastrophic outcome had already eroded Brock's credibility.

Legal Proceedings and Strategy

Valdivia's historic outcome can be traced to a plaintiff presentation that felt urgent and human, a defense that appeared dismissive, and courtroom moments that left jurors with little doubt about the severity of harm.

Plaintiff's Compelling Narrative

From opening statements, plaintiffs anchored the case in Brock's culture of unsafe shortcuts. They described a job site where a coworker was known as a "walking hazard" yet remained on scaffolding duty.

Internal safety manuals and email threads, introduced alongside expert testimony, showed written rules that contradicted daily practice. Counsel labeled the conduct "beyond gross negligence," positioning Brock's failures as inevitable precursors to disaster rather than an unfortunate lapse.

The focus then shifted to Valdivia himself. Photos of the 28-year-old welding student before the accident were contrasted with videos of his wheelchair-bound life after—his sister leaving college to become a caregiver, his parents lifting him into a van.

This storytelling, backed by neurologists and life-care planners, persuaded jurors that compensatory figures must cover decades of round-the-clock support. When Brock's managers tried to characterize the event as minor, plaintiffs highlighted post-incident efforts to "sweep the incident under the rug," reinforcing the theme of systemic indifference.

Decisive Trial Moments

The multi-day jury trial that ended in early 2025 built toward a single visual: a day-in-the-life montage showing Valdivia's daily routine of assisted feeding and physical therapy.

Courtroom observers noted audible gasps when the footage paused on a close-up of his tracheostomy scar.

Earlier, plaintiffs had used Brock's own safety supervisor to chart every missed inspection, turning a company witness into a reluctant advocate for the plaintiff's timeline.

Although exact deliberation hours remain sealed, jurors returned the unanimous verdict and record-setting damages on the same afternoon they received the case, indicating that liability was never in serious doubt.

The Historic Verdict

A Lake Charles jury delivered Louisiana's largest single-plaintiff personal injury award: $411 million for José Valdivia. The verdict recalibrated how catastrophic injury claims get valued across the industry.

The numbers reveal the extraordinary scope of the award. Valdivia, a 28-year-old scaffold builder, will need round-the-clock medical care for life. Jurors assigned $16.5 million to cover that lifetime care, lost wages, and other economic losses.

The remaining $394.5 million went to pain, suffering, and loss of enjoyment; more than 95% of the total award. That's a multiplier of roughly 663 times past medical expenses (over $594,000), far beyond the 3-to-5-times benchmarks typical even in nuclear verdicts.

The ripple effects started immediately. Before Brock, Louisiana's top single-plaintiff injury award was less than half this figure. Within weeks of the Valdivia judgment, plaintiff demand letters in unrelated refinery and maritime cases referenced the $411 million benchmark when proposing reserves.

Regional coverage analyses highlight the rise of such nuclear verdicts in Louisiana, though specific insurance industry responses to this verdict are not detailed.

Insurance Coverage Litigation

Before trial, Valdivia offered to settle multiple times within the combined policy limits. No money ever reached the table. Valdivia's lawyer called the refusal "kind of crazy," underscoring how the insurers' gamble opened Brock to a verdict forty times larger than its primary coverage.

Settlement windows closed in succession—first six months after suit was filed, then again on the eve of jury selection—yet the carriers held to a no-pay posture.

That decision now fuels separate bad-faith claims, with Brock arguing the insurers' rigid stance breached their duty to protect the insured from excess exposure.

The same facts created two disputes: liability and which of the insurers would pay.

Carrier vs. Carrier Disputes

Brock Services had two insurance providers that were involved in the coverage dispute.

Everest Insurance DAC provided directors-and-officers liability coverage with a five-year extended reporting period.

Ascot Syndicate 1414 served as Brock's excess liability insurer, providing coverage above the primary insurance layers. When the $411 million verdict hit, these two insurers launched competing legal strategies to avoid payment, rather than coordinating coverage.

Everest struck first, filing a declaratory action built on its "insured-vs-insured" exclusion. The carrier argued that since the refinery owner and several Brock affiliates all qualified as "Company" under the policy, Valdivia's personal-injury suit amounted to an impermissible intra-insured dispute. This interpretation would bar any obligation to defend or indemnify the claim entirely.

Ascot took a different approach, focusing on exhaustion requirements. The excess carrier pointed to policy language stating "our duty to defend ends once the Limit of Liability is exhausted by payment of judgments or settlements."

Through its own declaratory filing, Ascot insisted that Everest and any primary carriers must fully exhaust their coverage before excess obligations could attach.

Both carriers sought intervention in the underlying tort suit and pressed for early summary judgment.

Coverage Law Implications

For Louisiana coverage practitioners, the dispute spotlights three recurring themes.

First, follow-form excess policies are only as broad as the primary language they incorporate. If exclusions wipe out the foundation, upper layers may never attach.

Second, exhaustion requirements remain strictly enforced—Ascot's position that payment, not mere liability, must deplete underlying limits mirrors prevailing Fifth-Circuit authority.

Third, the case reaffirms a carrier's duty to settle: when liability is reasonably clear and damages dwarf limits, refusing a within-limits offer can invite nuclear verdicts and subsequent bad-faith penalties.

Key Takeaways from the Brock Services Lawsuit

As you evaluate catastrophic workplace claims after Brock v. Brock Services, two clusters of lessons emerge—one for plaintiff teams determined to secure full value and another for defense counsel hoping to avoid repeating the $411 million mistake.

Plaintiff Victory Blueprint

Winning a nuclear verdict begins with exhaustive evidence preservation. Trial counsel subpoenaed months of internal emails, safety manuals, and job-site photographs before Brock could "clean the file," then highlighted contradictions between written policies and the lax reality on the scaffold deck.

Medical experts and life-care planners translated José Valdivia's paralysis into lifetime costs, while videos of his daily struggles supplied the jury with visceral context.

When Brock's insurers refused multiple policy-limits offers, counsel kept that fact in evidence, framing the defense as unreasonable.

Defense Counsel Warnings

The Brock defense offers a cautionary catalogue of what not to do. Questioning the authenticity of catastrophic injuries—suggesting Valdivia was "faking" despite unrefuted imaging and wheelchair dependence—undermined their credibility.

A rigid denial of liability, unsoftened by safety reforms or empathy, fed juror anger already primed by Louisiana's growing appetite for nuclear verdicts. Coverage counsel's failure to appreciate trial exposure led insurers to reject a reasonable settlement, leaving Brock personally exposed to a nine-figure judgment.

Future Outlook and Practice Considerations

You now practice in a state where a single scaffolding accident produced a $411 million jury award.

Plaintiffs cite the verdict to justify higher demands, while insurers recalibrate reserves and treat any refusal to settle within limits as a potential path to a nuclear result.

For employer counsel, immediate priorities are clear: commission a top-to-bottom safety audit of all elevated-work operations, verify incident-reporting workflows capture near-miss data in real time, and preserve digital safety logs for at least seven years.

Audit insurance programs to confirm excess limits match catastrophic-injury exposure and map notice obligations across every layer. Coverage litigation involving Everest, and in some cases other insurers, illustrates how endorsement gaps or late notice can strand defendants without a defense.

Track appellate review of the general-damages multiplier and monitor declaratory-judgment filings that may redefine duty-to-settle standards. The safest course is early case valuation, documented attempts to engage all carriers, and a standing authority ladder that allows you to accept policy-limits offers within days rather than months.

.webp)

.webp)