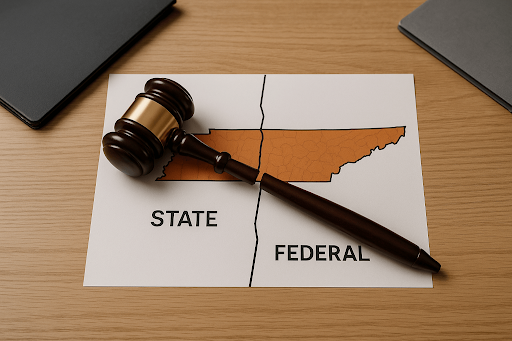

Nevada imposes a two-tier statutory cap on punitive damages: three times compensatory damages, or $300,000, when compensatory awards fall below that amount. The current framework, established through 1995 amendments to Nevada Revised Statutes (NRS) Chapter 42, introduced the clear and convincing evidence standard for proving malice, fraud, or oppression.

This article outlines Nevada’s statutory limits, key exceptions, procedural rules, and major cases shaping punitive damages in 2025.

Legal Foundation of Punitive Damage Caps in Nevada

Nevada’s punitive damage framework is governed entirely by statute under NRS Chapter 42, with no constitutional limitations on legislative authority. The current structure originates from 1995 revisions to Chapter 42, which introduced the two-tier cap system and codified the clear and convincing evidence standard for proving fraud, malice, or oppression.

- § 42.005(1) permits punitive damages only where it is proven by clear and convincing evidence that the defendant has been guilty of oppression, fraud, or malice, express or implied.

- § 42.001(2)–(4) defines fraud, malice, and oppression as intentional misrepresentation, despicable conduct with conscious disregard, and unjust hardship with conscious disregard, respectively.

The Nevada Supreme Court has upheld this statutory scheme under both state and federal due-process standards. In Franchise Tax Bd. of California v. Hyatt (2014), the court found no Fourteenth Amendment violation, and in D.R. Horton, Inc. v. Betsinger (2014), it reaffirmed bifurcation and entitlement requirements under NRS 42.005(3).

2025 Punitive Damage Caps in Nevada

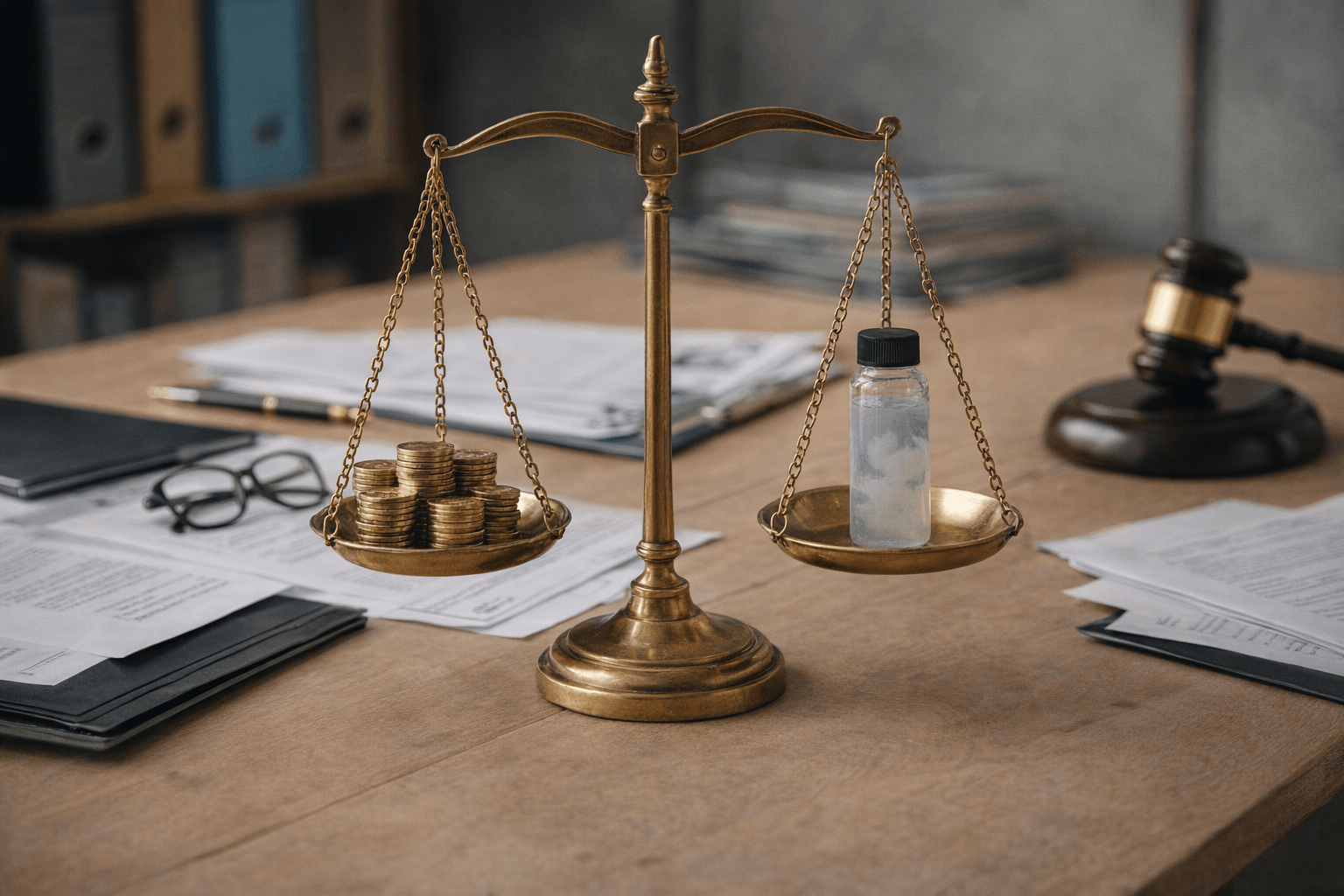

The current framework operates under a two-tier formula:

General Civil and Personal Injury Cases:

- Standard Cap: If compensatory damages are $100,000 or more, punitive damages are capped at three times compensatory (NRS 42.005(1)(a)).

- Lower-Tier Cap: If compensatory damages are less than $100,000, punitive damages are capped at $300,000 (NRS 42.005(1)(b)).

Complete Exceptions (Uncapped Categories):

- Defective products, insurer bad faith, specific housing-discrimination claims, toxic/hazardous emissions, and defamation are expressly exempt from the caps under NRS 42.005(2).

Further stipulations include:

DUI-Related Conduct:

- NRS 42.010 governs punitive damages for injuries caused by the operation of a vehicle after consuming alcohol/other substances, and it expressly states that NRS 42.005 does not apply to actions under this section.

Elder Abuse and Exploitation:

- NRS 41.1395 provides enhanced remedies for elder abuse (double actual damages and attorney's fees) but does not create separate punitive damages provisions. Punitive damages claims in elder abuse cases remain subject to NRS 42.005's general framework and caps.

Judicial and Jury Requirements:

- Bifurcation: Under NRS 42.005(3), entitlement is decided first; if punitive damages are warranted, a subsequent proceeding determines the amount, and financial condition evidence is barred until that second phase.

- No Cap Instruction: Civil proceedings for punitive damages in Nevada follow strict procedural rules under NRS 42.005(3). Entitlement must be decided before the amount, and civil verdicts require agreement by three-fourths of jurors, not unanimity.

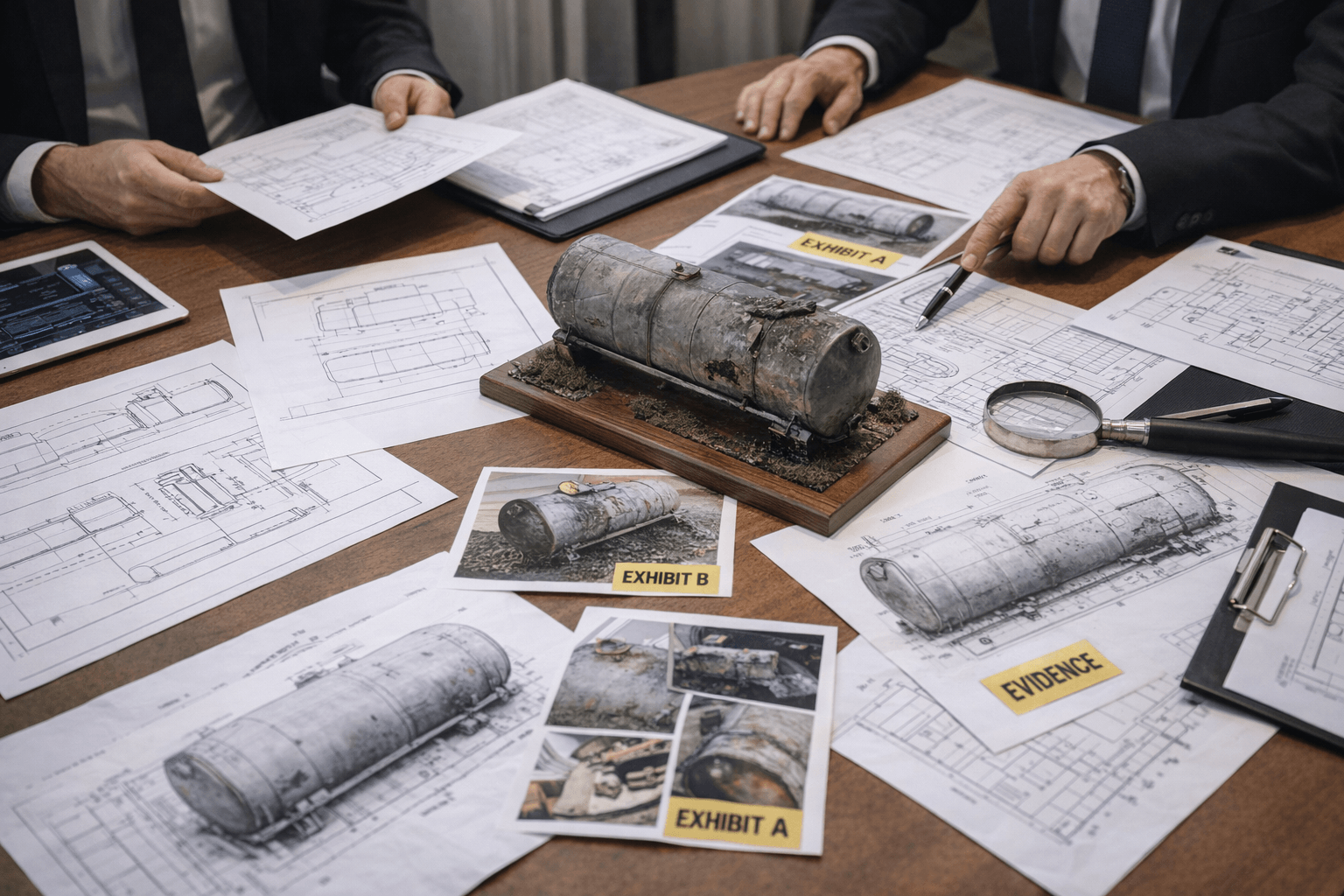

Procedural & Evidentiary Requirements for Punitive Damage Caps in Nevada

Under NRS 42.005, punitive damages in Nevada require clear and convincing evidence of fraud, malice, or oppression—conduct showing conscious disregard for others’ rights or safety.

- Pleading Standards: Punitive claims must include specific facts, not conclusions. NRCP 9(b) requires particularity in fraud allegations, while NRS 41A.071 mandates an expert affidavit with medical-malpractice complaints.

- Financial Discovery Restrictions: Evidence of a defendant’s financial condition is excluded until entitlement to punitive damages is established. Courts typically require a heightened showing before allowing wealth-related discovery, preventing premature or invasive requests.

- Mandatory Bifurcation: Under NRS 42.005(3), trials proceed in two stages—liability first, damages second. Financial evidence becomes admissible only in the second phase, and juries may not be advised of statutory cap amounts at any point.

These safeguards ensure that punitive damages in Nevada are reserved for conduct involving genuine malice or conscious wrongdoing, while maintaining fairness in both discovery and trial proceedings.

Recent Developments and Pending Legislation in Nevada

Nevada’s 2023–2025 legislative cycle introduced limited but meaningful updates to punitive damages law. Two measures are particularly noteworthy:

- Senate Bill 67 (2025): Pending before the Nevada Legislature, this proposal would revise special verdict forms and indemnification provisions affecting state and local entities. If enacted, it could expand indemnification rights for public hospitals and government-operated healthcare facilities in punitive-damage cases.

- Senate Bill 401 (2023): Effective July 1, 2023, this amendment to NRS 42.010 removed the prior requirement that defendants knew a person would operate a vehicle or vessel while under the influence before punitive damages could be awarded. The change broadens potential exposure for bars, social hosts, and commercial establishments in alcohol-related injury actions.

NRS 42.005 remains unchanged, preserving the two-tier cap of three times compensatory damages or $300,000 for smaller awards. Further reforms may follow as legislators consider updates to public-entity and tort reform.

Key Nevada Punitive Damage Cases

The following Nevada Supreme Court decisions define the state’s modern punitive damages framework, clarifying evidentiary standards, procedural requirements, and limits on recovery under NRS 42.005.

Ainsworth v. Combined Insurance Company of America: Insurance Bad Faith Foundation

In Ainsworth v. Combined Insurance Company of America (1989), the Nevada Supreme Court reinstated a punitive award of nearly $6 million against an insurer for bad faith conduct. The court held that insurers face punitive liability when their conduct demonstrates malicious intent, fraud, oppression, or conscious disregard of the insured's interests.

Ainsworth provides the framework for pursuing punitive damages in personal injury cases involving insurance bad faith, which frequently accompanies catastrophic injury claims.

Craigo v. Circus-Circus Enterprises: Actual Malice Requirement

In Craigo v. Circus-Circus Enterprises (1990), the Nevada Supreme Court refined the definition of malice required for punitive damages, holding that malice requires actual ill will or intent to harm, rather than the implied malice standard used in other tort contexts.

The court rejected punitive damages based solely on negligent security, requiring proof of actual malicious intent rather than gross negligence or recklessness. Craigo establishes the evidentiary standard for punitive damages, particularly in medical malpractice cases where simple errors cannot support punitive damages without evidence of knowing wrongdoing or deliberate indifference to patient safety.

Together, these rulings define the evidentiary and procedural boundaries for punitive damages under Nevada law.

Practical Application of Nevada’s Punitive Damage Caps

Nevada’s punitive damages framework under NRS 42.005 sets a high bar: plaintiffs must prove fraud, malice, or oppression through clear and convincing evidence that the defendant consciously disregarded known risks. This standard, reinforced by bifurcated trials and restrictions on financial-condition evidence, makes case preparation a matter of precision and timing. Courts further apply proportionality review to ensure awards remain constitutionally sound.

Success in this environment depends on how effectively legal teams build and manage evidence. Organizing records, tracing intent, and demonstrating awareness of harm all require speed and accuracy—areas where AI-powered systems like Tavrn now play a central role. By streamlining record retrieval and chronology development, they help practitioners meet Nevada’s demanding evidentiary standards with clarity and confidence.

.webp)

.webp)