Tennessee imposes a statutory cap on punitive damages, limiting awards to the greater of two times compensatory damages or $500,000. Four statutory exceptions remove this cap entirely.

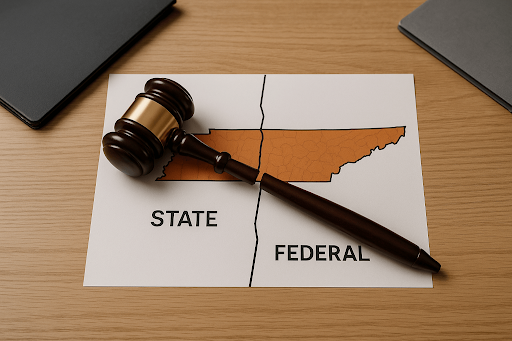

A key distinction arises from the Sixth Circuit’s 2018 Lindenberg v. Jackson National Life Insurance Co. (2018) decision, which struck down the cap in federal diversity cases, while Tennessee state courts continue to enforce it. This split directly affects case valuation and forum strategy.

This article explains Tennessee’s punitive damage framework, statutory limits, procedural rules, recent legislative updates, and leading court decisions shaping enforcement in 2025.

Legal Foundation of Punitive Damage Caps in Tennessee

Tennessee’s punitive damage framework is entirely statutory, established under TCA § 29-39-104 as part of the Civil Justice Act of 2011. The statute reflects the Legislature’s authority to regulate civil remedies and balance deterrence with due process.

Core legal principles:

- Purpose: Punitive damages serve to punish egregious misconduct and deter future violations, not to compensate plaintiffs.

- Proof standard: Plaintiffs must present clear and convincing evidence of intentional, fraudulent, malicious, or reckless conduct before punitive damages may be awarded.

- Constitutional review: Courts must ensure awards comply with federal due process standards, applying the BMW v. Gore (1996) factors — reprehensibility, ratio to actual harm, and comparison to similar civil penalties.

- Forum split: Tennessee state courts uphold the statutory cap, while the Sixth Circuit’s 2018 Lindenberg v. Jackson National Life Insurance Co. decision invalidated it in federal diversity cases, creating a lasting state-federal divide.

In practice, this framework balances punishment and deterrence with procedural safeguards, though the Lindenberg ruling continues to shape forum choice and settlement strategy across Tennessee.

2025 Punitive Damage Caps in Tennessee

Tennessee caps punitive damages at the greater of two times total compensatory damages or $500,000. The cap applies to combined economic and non-economic damages. For instance, a $300,000 compensatory award allows up to $600,000 in punitive damages, while any award below $250,000 defaults to the $500,000 floor.

Exceptions — No Cap Applies When:

- The defendant intentionally inflicted serious physical injury.

- The defendant falsified, destroyed, or concealed records to evade liability.

- The defendant was under the influence of alcohol, drugs, or another intoxicant, impairing judgment and causing injury or death.

- The defendant’s conduct resulted in a felony conviction, causing the plaintiff’s harm.

Judicial Oversight: Courts must ensure all punitive awards satisfy constitutional due-process limits under BMW v. Gore, reviewing:

- The reprehensibility of the conduct

- The ratio of punitive to actual harm

- Comparisons to similar civil penalties

Appellate courts may order remittitur if awards exceed statutory or constitutional boundaries.

Mandatory Bifurcation: Punitive claims are tried in two phases:

- Phase I determines liability and compensatory damages

- Phase II determines punitive amounts.

Juries are not informed of the statutory cap during deliberations.

Procedural & Evidentiary Requirements in Tennessee

Tennessee imposes strict procedural safeguards for punitive damages, requiring clear and convincing evidence that a defendant acted intentionally, fraudulently, maliciously, or recklessly—a higher standard than preponderance but lower than beyond a reasonable doubt.

Pleading & Proof Standards:

- Under Rule 8.01, plaintiffs must include a demand for judgment but need not state a specific dollar amount.

- In health-care liability cases, a specific sum may be pled but cannot be disclosed to the jury.

- Complaints must allege facts supporting one of the four statutory mental states; no pre-trial evidentiary showing is required beyond standard pleading.

Evidentiary Restrictions:

- Evidence of a defendant’s net worth or financial condition is inadmissible in Phase I and considered only in Phase II after liability is established.

- Jurors receive special instructions outlining the clear-and-convincing standard and the Hodges factors, which include:

- The nature and reprehensibility of the conduct

- The relationship between the parties

- The defendant’s awareness and motive

- Financial condition, prior punitive awards, remedial actions, and deterrent effect.

- Special verdict forms separate findings on punitive liability and amount.

These safeguards ensure that punitive awards in Tennessee remain defensible, proportionate, and constitutionally sound.

Recent Legislative Developments in Tennessee

Between 2023 and 2025, Tennessee enacted four laws expanding punitive damages availability across new causes of action:

- SB 0542 (2023): Created wrongful-adoption claims, allowing punitive damages and a minimum $100,000 liquidated damages (effective July 1, 2023).

- SB 0466 (2024): Added punitive remedies for online harm to minors and permitted class-action certification (effective May 17, 2024).

- SB 2743 (2024): Expanded private-property-rights protections, authorizing punitive damages against state agencies implementing certain international policies (effective July 1, 2024).

- HB 1264 (2025): Authorized punitive damages against political subdivisions for related violations (effective July 1, 2025, applying to new or renewed contracts).

These enactments broaden punitive damages exposure without altering Tennessee’s core cap: the greater of two times compensatory damages or $500,000, subject to existing exceptions for serious injury, destruction of evidence, intoxication, or felony conduct.

Key Tennessee Punitive Damage Cases

Tennessee’s case law defines the constitutional and procedural boundaries of punitive damages, with federal-state tension central to modern practice.

Lindenberg v. Jackson National Life Insurance Co. — State-Federal Split

In Lindenberg v. Jackson National Life Insurance Co., 912 F.3d 348 (6th Cir. 2018), the Sixth Circuit struck down Tennessee’s punitive-damage cap as violating the state constitution’s jury-trial guarantee, holding it impermissibly limited jury authority. The ruling applies only in federal diversity cases.

By contrast, the Tennessee Supreme Court in McClay v. Airport Management Services, LLC, 596 S.W.3d 686 (Tenn. 2020) upheld noneconomic-damage caps, signaling likely support for the punitive framework. Tennessee courts continue enforcing TCA § 29-39-104 absent contrary state precedent.

McClay v. Airport Management Services — Constitutional Validity Signal

In McClay v. Airport Management Services, LLC, the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld statutory caps on noneconomic damages, rejecting challenges based on jury-trial, separation-of-powers, and equal-protection grounds.

Although McClay did not directly address punitive caps, the Court criticized the Sixth Circuit’s reasoning in Lindenberg and strongly suggested Tennessee’s punitive-damages cap would withstand state constitutional scrutiny. As a result, state courts continue to enforce TCA § 29-39-104, even as federal courts disregard it under Lindenberg.

Wilson v. Americare Systems — Pleading and Verdict Requirements

Building on Hodges v. S.C. Toof & Co., 833 S.W.2d 896 (Tenn. 1992), the Tennessee Supreme Court in Wilson v. Americare Systems, Inc., 397 S.W.3d 552 (Tenn. 2013) reaffirmed that punitive damages require clear and convincing evidence of intentional, fraudulent, malicious, or reckless conduct.

The Court emphasized mandatory bifurcation, detailed jury instructions incorporating the Hodges factors, and special verdict forms separating findings on liability and amount. Awards remain subject to TCA § 29-39-104’s statutory cap, unless one of the four statutory exceptions applies, allowing uncapped punitive damages.

Practical Applications of Tennessee’s Punitive Damage Caps

Tennessee’s statutory cap and clear-and-convincing-evidence requirements make successful punitive-damage claims hinge on precise pleading, detailed documentation, and disciplined trial preparation. Courts enforce bifurcation and evidentiary limits strictly, requiring airtight support from the initial filing.

In personal-injury litigation, meeting the intentional, fraudulent, malicious, or reckless-conduct standard under TCA § 29-39-104 demands comprehensive medical and factual records demonstrating the defendant’s conscious disregard of known risks. Evidence of financial condition remains limited to Phase II, reinforcing the need for organized, defensible proof.

Legal teams increasingly rely on fast medical record retrieval and structured chronologies to meet Tennessee’s heightened evidentiary standards. Platforms such as Tavrn help streamline record review, manage complex documentation, and strengthen arguments from discovery through trial.

.webp)

.webp)